Using integrals to find sum of squares closed form

As with all my posts here I’ll try to give a more verbose version of what the book covers; specifically how to get the sum of squares closed form using “Method 4: Replace sums by integrals”. All the book explains is finding the error in the approximation and the approximation itself.

This post assumes you have the book to hand although hopefully it’s readable on it’s own. Any mistakes in this text are my own.

In Concrete Mathematics (Knuth, Graham, Patashnik) they use integrals to as a stepping stone to find the closed form for the sum of squares. I am not as eloquent as they are so I’ll just quote them here

In calculus, an integral can be regarded as the area under a curve, and we can approximate this area by adding up the areas of long, skinny rectangles that touch the curve. We can also go the other way if a collection of long, skinny rectangles is given: Since $\unicode{9744}_n$ is the sum of the areas of rectangles whose sizes are $1 × 1$, $1 × 4$, . . . , $1 × n^2$, it is approximately equal to the area under the curve $f(x) = x^2$ between $0$ and $n$.

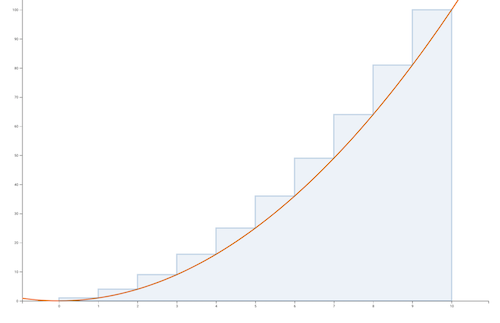

I am not even going to try and replicate the graph in the book so here is one made with mathisfun.com integral approximation calculator. The area under this graph is approximately $\unicode{9744}_n$

This post covers the first “sub-method” in Method 4: Replace sums by integrals

Method 1 - Examine Error in Approximation $n^3/3$

What confused me is this is not exactly the same as counting the error wedges on the beautiful graph in the book (that comes in the next method). This is literally the error in our first pass closed form approximation using the integration rules where the area under $x^2$ is $\int x^2dx = n^3/3$. Thus we know the sum of squares is approximately $\frac{1}{3}n^3$.

Thus the error in approximation is $E_n = \unicode{9744}_n - \frac{1}{3}n^3$ and therefore $E_{n-1} = \unicode{9744}_{n-1} - \frac{(n-1)^3}{3}$. Rearranging we get $\color{green}{\unicode{9744}_{n-1} = E_{n-1} + \frac{(n-1)^3}{3} }$

We also know what $\color{red}{\unicode{9744}_n = \unicode{9744}_{n-1} + n^2}$. The book then very elegantly puts this all together to find a simple recurrence for $E_n$ as follows

\[\begin{align} E_n &= \unicode{9744}_n - \frac13 n^3 = \color{red}\unicode{9744}_{n-1} + n^2 \color{#3d4144} - \frac13 n^3 \\ &= \color{green}E_{n-1} + \frac{(n-1)^3}{3} \color{#3d4144}+ n^2 - \frac13 n^3 \\ &= E_{n-1} + n - \frac13 \end{align}\]Method 2 - Summing Wedge Shaped Error Terms

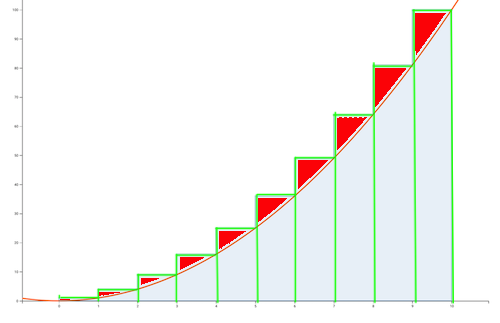

This means summing the error shaped wedges above the curve

What I needed some pondering to understand is that a given rectangle is $x^2$ and the area under the curve for that section is is $\int_{k-1}^kx^2dx$. What we are doing is subtracting the latter from the former to find the error wedges. Thus in total the full error would be

\[E_n = \unicode{9744}_n - \int_0^n x^2dx\]Now let’s step-wise sum of each $x^2$ rectangle and that sections portion under the curve using the same colours as in the graph

\[\definecolor{squared}{RGB}{143,232,128} \definecolor{under_curve}{RGB}{118,187,237} \begin{align} \sum^n_{k=1}(\color{squared}k^2\color{#3d4144} - \color{under_curve}\int_{k-1}^k x^2dx \color{#3d4144}) \end{align}\]Then, by using the rules of integration to find the anti-derivative of something squared, we will find the area under graph of just that section $\int_{k-1}^k$

\[\definecolor{squared}{RGB}{143,232,128} \definecolor{under_curve}{RGB}{118,187,237} \begin{align} \sum^n_{k=1}(\color{squared}k^2\color{#3d4144} - \color{under_curve}\frac{k^3}{3} - \frac{(k - 1)^3}{3} \color{#3d4144}) \end{align}\]And finally we land at our error in the approximation recurrence again

\[\sum_{k=1}^n k-\frac13\]Stepping Stone: Finding $E_n$ Recurrence Closed Form

Therefore if we could just find the closed form of $E_n$ we can find the closed form of $\unicode{9744}_n$ because we can do $\unicode{9744}_n = E_n + \frac13 n^3$. Let’s break the recurrence $E_n$ down to it’s component bits

- $E_{n-1} + n$ - Here we are just summing in which we can do with Gauss’ formula: $n(n-1)/2$

- $\frac13$ - This is just a constant so to find the sum we simply multiply by how many times we’re summing so $n \cdot \frac13$

THUS our $E_n$ closed form is

\[E_n = \frac{n(n+1)}{2} - \frac{n}{3}\]Tying it Together: Using $E_n$ to Find $\unicode{9744}_n$ Closed Form

We can prove $E_n$ closed form works via some induction I’ll add at the end to avoid distracting from the main topic. So, finally, our $\unicode{9744}_n$ ends up being

\[\unicode{9744}_n = \frac{n(n+1)}{2} - \frac{n}{3} + \frac13 n^3\ \ \ \ \ \text{for }n \geq 0\]Which is equivalent to what the book provides in equation 2.39

\[\unicode{9744}_n = \frac{n(n+\frac12)(n+1)}{3}\ \ \ \ \ \text{for }n \geq 0\]TODO: Convert from the form I have above to the book’s closed form 2.39.

Appendix: Induction Proof of $E_n$

For the recurrence $E_n = E_{n-1} + n - \frac13$ we find that the closed form is $E_n = \frac{n(n+1)}{2} - \frac{n}{3}$. This checks out via the following induction proof (following the same process as in my super simple induction post)

\[\begin{align} \frac{n(n + 1)}{2} - \frac n3 &= \frac{(n-1)n}{2} - \frac{n-1}{3} + n - \frac13 \\ \frac{3n(n+1) - 2n}{6} &= \frac{3n(n-1) -2(n-1) +6n -2}{6} \\ \frac{3n^2 + 3n - 2n}{6} &= \frac{3n^2 - 3n - 2n + 2 + 6n - 2}{6} \\ \frac{3n^2 + n}{6} &= \frac{3n^2 + n}{6} \\ \end{align}\]And RHS is the same as LHS so closed form is OK.